#TechnicalTests: Does Google Use Page Visits in Its Algorithm?

We’re lucky to have an incredibly senior team of technical SEO consultants at Propellernet, with over 50 years’ experience between them. Over the last few months, the team has been testing various theories about Google’s algorithm to bring an even deeper level of knowledge to our clients. In the first of our #TechnicalTests series, SEO consultant, Robin Fry, investigates assumptions around the impact of page visits on rankings.

It’s often posited that Google’s algorithm uses the amount of traffic to a page to assess how popular a piece of content is and how interesting people are likely to find it. But I have seen no hard evidence of this myself. Not being one to believe anything I haven’t seen with my own eyes, I decided to do a little test to see if visits to a web page really do help its content to rise in the ranks of Google results.

Please note: when I say “little” test, that’s not just an affectation; this really was a small test just to satisfy my curiosity. It has led me to draw some conclusions, but I’d like to run a larger scale version of this experiment to get some really solid answers to back those conclusions up. At least I’d like to, but I’ll need to rethink some of my methods. But there were results for sure, and I can even throw in a cautionary tale as a special bonus.

To test this out quickly, I needed to find a search query which was rare enough that it would be fairly easy to appear on the first page of Google results for it, but not so rare that there was no competition at all. As a very random test, I typed a name into Google that I thought I’d just made up – “Jim Billock”. Turns out there are some Jim Billocks in the world.

Apologies if you are reading this and you happen to be a Jim Billock, but there aren’t that many of you and your online presence is pretty minimal, so I’m afraid I took your name in vain for the purposes of this test.

The search also brought up results for an actor called Jim Bullock, so it perfectly fitted my needs – some, but not too much, competition, most of which wasn’t actively optimised for search. Which was very lucky, as I thought I was going to have to spend a lot longer making up silly names (sorry again, Jim) and typing them into Google.

So now I had my subject matter, I needed some content. To get a real sense of whether click-throughs make a difference, I decided to create two pages on separate sites, linked to from another distinctly separate site. I could then test what changed when one page received referral traffic and the other didn’t (more on how I did that and the lessons I learned later).

First, I built the site that had the links on it. Each of the sites was built in WordPress. I wanted to include content on the source site, so that Google wouldn’t just ignore it. To make sure it didn’t get too much “accidental” traffic, thus skewing the test results, I returned to my method of using randomly made-up words on page names and content. But this time I needed words that no one was ever likely to type into a browser or search engine, even by accident. Hence, “Shmagungle”, with two separate pages of nonsense content called “Herfmarmanunga” and “Zspervorance”. I’m fairly confident none of those are widely-used expressions, but please do let me know if I’m wrong.

The content on the pages was equally silly, just to ensure there wasn’t much likelihood of them appearing in search results for anything – this was a test of link traffic rather than whether those links passed authority, or “link juice”, so I was keen for this site not to perform well in search, to keep the test as clean as possible. Both pieces of content contained a single reference to “Jim Billock”, which I would use as the link anchor text for my test.

With those pages built, I then created two separate sites, each with a page of unique and similarly nonsensical content about Jim Billock (who, in this incarnation, I decided was a “sandwich artist” – I don’t know how or why I come up with this rubbish, to be perfectly frank). Then I added the links from the “Jim Billock” anchor text, one to each of these two sites from a separate page on the original site. I left them for a while, just long enough to get crawled and indexed by Google and to start appearing around the bottom of the first page of Google results for “Jim Billock”.

Now I just needed to test the value of click-throughs by actually getting some clicks through one of the links, and seeing if that helped the linked site gain visibility faster than the one that wasn’t getting referral traffic.

This is where the cautionary tale comes in.

To get a good number of clicks through the links, from a “natural” spread of locations and IP addresses in a short space of time, I decided to make use of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. I would set up a request for people to click the link on one (and only one) of the two pages, so that I could see what difference that made, if any. This seemed like a sensible approach, and my colleagues agreed.

“But Robin”, I hear you say, “getting people to drive clicks through to a website is explicitly against Mechanic Turk’s Terms of Service!”

Yeah. I should’ve read those.

Long story short, I managed to get myself banned from using Mechanical Turk. Don’t try this at home kids, and always read the small print.

But, before that happened, I was able to get some click-throughs, on two separate occasions (one for each site). This was enough to spark some interesting changes in search rankings for both pages, and even for the homepages of those websites, in the “Jim Billock” SERPs (the irony is not lost on me that this very page may outdo them both now, as I’ve spammed it with that name so many times).

Here’s what happened:

First off, I got people to visit the “Shmagungle” site, go to the “Herfmarnanunga” page and click on the “Jim Billock” link (I really should have considered the fact that eventually I was going to have to write these names out, multiple times, in a mostly serious blog post), which took them to the “Jim Billock fan page” at https://www.pnettest4.co.uk/who-is-jim-billock/. I asked users to tell me what they saw on the page, to give the task at least a modicum of meaning and to ensure they had arrived at the right spot. Again, don’t do this, you’ll get in trouble; I shouldn’t have done it and my only excuse is ignorance.

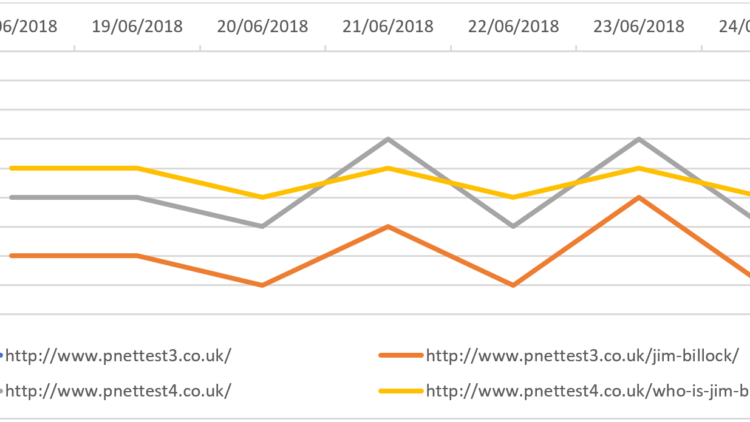

This drove over 250 clicks to the page, between the 12th and 15th of June 2018. The page in question had settled at 5th position in Google results for “Jim Billock” pretty soon after it was published (the yellow line in the graph below), and had remained there on a daily basis for a few weeks. It stayed there for a few more days after the boost in click-throughs. The homepage of that site had similarly settled in 6th place, signified by the grey line in the graph below. Interestingly, perhaps, there was a slight blip on the 17th June when that page dropped down to 7th place. However, it was back at 6th position the following day and this may have just been a coincidence.

What is far more interesting is what happened a few days later. On the 20th of June, both the page that had received the click-throughs and its home page dropped by one position, as did the page on the other site, https://www.pnettest3.co.uk/jim-billock/, which had not been the recipient of any click-through traffic. That page is represented by the orange line on the graph below. The following day, the recipient page had gone back up to 5th place in Google, but had been overtaken by its homepage, which had leapt up from 7th place to 4th. The page on the other site, which still hadn’t received any click-throughs, or indeed any significant traffic, also went up in the ranks by two places. The homepage for that site didn’t rank anywhere on the first ten pages of “Jim Billock” results.

Now, as I said at the start, this is too small a test to draw any rock-solid conclusions from, but these movements at least seem like more than pure coincidence. Each page had sat quietly at the same position in the SERPs for “Jim Billock” for several weeks. They had received little to no traffic, referral or otherwise, during that time. Then, within a few days of increased click-through activity to just one of those pages, their positions in Google started bouncing around. It really felt like Google was reacting to the clicks in some way.

The reaction seemed strange though. To be perfectly honest, I’d expected nothing to happen at all as a result of the clicks. I thought if there was to be any response at all, it would be limited to the page receiving the links, and the positions of the other pages would only be indirectly affected – i.e. if that page went up in the results, the others may be pushed down, or vice versa. What actually happened though, was that the three pages that were ranking all moved in the same direction – even the one that was on a different site. The only connection was that they were linked to from another site, which was also not appearing in the search results for “Jim Billock”. And the two pages that hadn’t received clicks were suddenly performing a little better than the one that had. This was totally unexpected.

While at this point I still hadn’t run afoul of Mechanical Turk’s T&Cs, I didn’t request any further clicks for the next few days, preferring to observe what happened next. Which was a little bit of up and down, with all three pages doing one or the other pretty much in sync:

The falls and rises for the page that had received all the referral traffic continued to have less pronounced peaks and troughs than the other two, which seemed strange to me. If this was indeed a result of the click-throughs, why were the other pages seeing a bigger effect? But it seemed unlikely that any other factors played a part – there were no other changes being made to any of these pages, they weren’t getting any additional traffic or links, and as far as I could see there weren’t any major changes happening to any of the other pages that appeared on the first page of Google for a search on “Jim Billock”.

On Monday 25th June, I decided to test what would happen if I drove clicks to the other site, through the other link on the “Zspervorance” page. I requested as much on Mechanical Turk, and shortly afterwards received an email to say my account had been suspended immediately for violating their terms of service. There were 25 referral visits to https://www.pnettest3.co.uk/jim-billock/ before that point, a much lower number than with the previous test, and with no real frame of reference it was impossible for me to gauge whether this would make a significant impact on search rankings. But let’s see.

So this is what happened next:

It certainly looked as though there may have been an initial boost to the ranking for https://www.pnettest3.co.uk/jim-billock/ a couple of days after the referral visits, while the page on the other site stabilised its position and the home page of that site jumped around quite erratically. Then they all dropped down again on the 29th.

Then it all went screwy:

The home page at https://www.pnettest4.co.uk/ dropped off of the first page of “Jim Billock” search results entirely, just for a day, on the 30th of June; it was halfway down the second page. It reappeared the following day, albeit at a lower position. The page that had all the clicks to begin with, https://www.pnettest4.co.uk/who-is-jim-billock/, slowly dropped down to the bottom of the front page from the 28th of June to the 3rd of July.

Meanwhile, the home page of https://www.pnettest3.co.uk/ came from out of nowhere to sit at 5th place, above the two pages that had actually received traffic through the links. If referral visits were being used by Google as a ranking factor, this seemed to suggest that the main domain saw a greater impact than the specific URL that received them.

Having been thrown off Mechanical Turk, I decided to let things play out. Okay, so I didn’t have much choice anyway, but I thought it prudent not to seek another means of artificially driving traffic through to these pages, however innocent my intentions.

Here’s what happened next:

One site (the one that had received far fewer referral visits) appeared to have won out over the other. The homepage of the losing site mainly floated around at the bottom of the first page of “Jim Billock” SERPs, while the page that had been the active recipient of a burst of referral traffic over a few days ranked lower than all of the others, even disappearing from SERPs completely from the 13th to the 16th of July. Was it being penalised by Google for this isolated and probably very suspicious-looking flurry of activity? It’s hard to say; it was certainly still being indexed by Google during this time, I could still find it in Google by searching for specific chunks of the content on the page and it reappeared on the front page on the 17th as if it had never been away.

There wasn’t much to report after this. The pages continued to rank on the first page of Google for “Jim Billock” most of the time, with the expected ups and downs and the pages on https://www.pnettest3.co.uk/ consistently outranking those on https://www.pnettest4.co.uk/.

I’m certainly not about to make any grand announcements about my findings here, especially as it was such a small test and was so brutally cut short as a result of my own hubris. However, the fact that these pages were all ranking, or not ranking, so consistently prior to my interference certainly suggests that Google’s algorithm does measure and monitor clicks through links and applies them to the algorithm somehow. As with most ranking factors, it also looks like Google will penalise a web page or site that appears to be cheating, which is only right and proper.

I would love to run this test on a grander scale and see if I can draw some more concrete conclusions. I’ll need to come up with a safer, more legitimate means of testing the power of referral clicks for SEO, while still trying to do so in as ‘sterile’ an environment as possible. That’s going to take some thought.

The main thing I’ve learned from this test is: always, always read the Terms & Conditions.